We are only beginning to see the legal fallout from the Supreme Court eliminating the constitutional right to an abortion.

The Comstock Act is one of the most laughably unconstitutional laws that is still part of the United States Code. Named after Anthony Comstock, who the Supreme Court once described as “a prominent anti-vice crusader who believed that ‘anything remotely touching upon sex was ... obscene,’” the law is vague, overbroad, and purports to make it a felony to mail a simply astonishing array of material.

Among other things, the act makes it a crime to mail any “lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy or vile article” (whatever that means). It prohibits mailing any “thing” for “any indecent or immoral purpose” (again, whatever that means). And, in a provision that largely sat dormant while Roe v. Wade was still good law, the Comstock Act purports to make it a crime to mail any “drug” that “is advertised or described in a manner calculated to lead another to use or apply it for producing abortion.”

But, of course, thanks to a Supreme Court dominated by Republican appointees, Roe is no longer good law. And that means that this prudish law named after an impossibly squeamish man is suddenly relevant again. Read broadly, the law could make distribution of abortion-inducing drugs incredibly complicated.

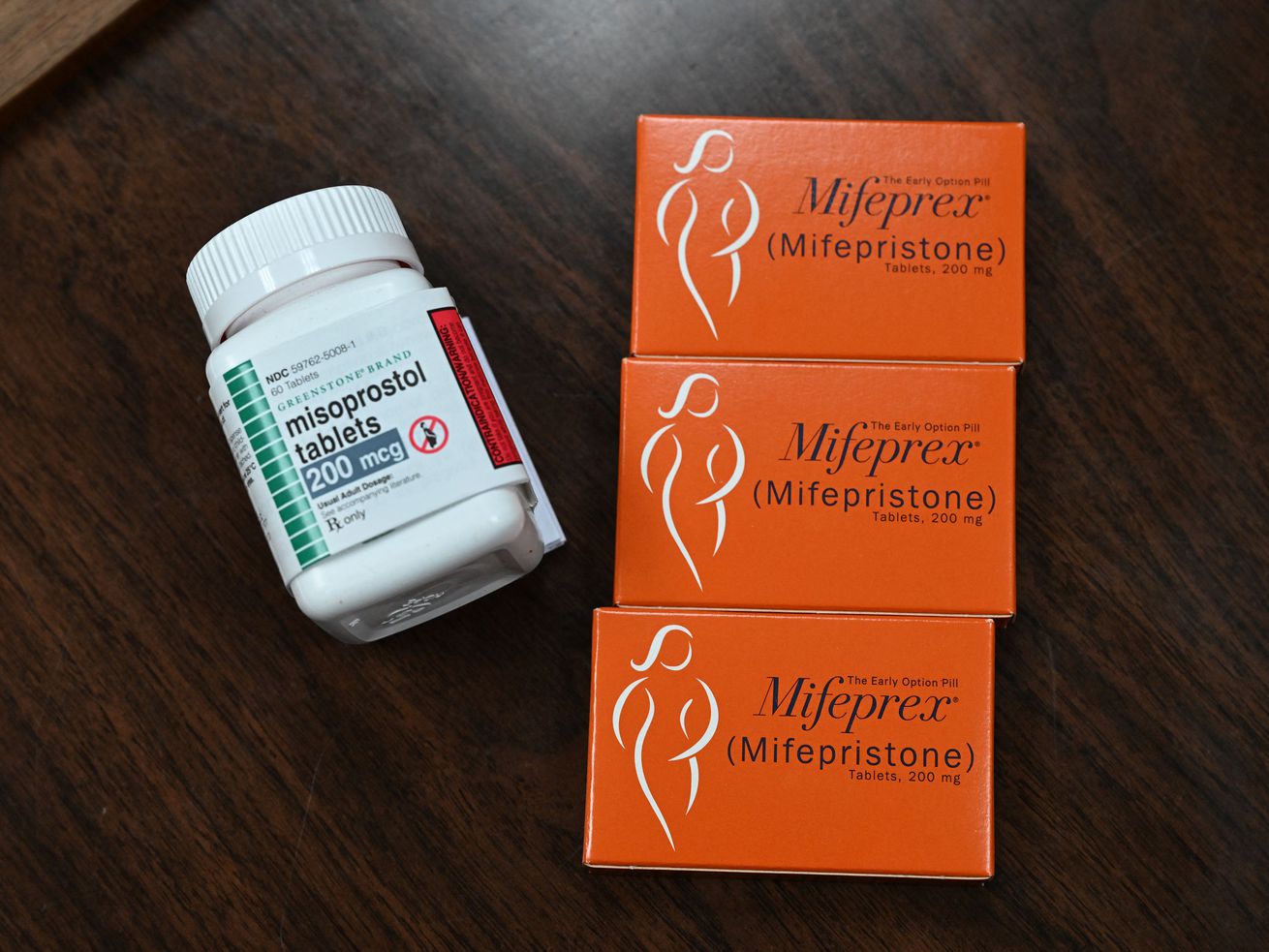

Medication abortions — that is, abortions induced by pills — account for more than half of all abortions in the United States.

As my colleague Rachel Cohen explained, medication abortion is also the next frontier in the anti-abortion right’s campaign against reproductive freedom. Even as the Biden administration attempts to expand access to abortion-inducing medication, mostly Republican lawmakers in mostly red states have ambitious plans to prevent patients from obtaining these drugs. According to the Guttmacher Institute, state lawmakers introduced 118 restrictions on medication abortions, across 22 different state legislatures, in 2022 alone.

Inevitably, the future of medication abortion will end up litigated in the courts. And important questions such as whether abortion medications can be shipped within the United States could easily come down to how a Republican-dominated judiciary wants to interpret the newly relevant Comstock law.

This uncertainty over an 1873 law, written by people who appeared unaware that the Bill of Rights exists, is a microcosm for a much broader problem facing abortion providers. When Roe fell, numerous state and federal abortion restrictions that were blocked by Roe suddenly came online. Many of these laws haven’t been interpreted by any court since 1973, when Roe eliminated the need to parse most anti-abortion statutes. Some of them were enacted when Roe was good law, and have never been interpreted by any court.

That means that abortion providers, including clinics and pharmacies that provide abortion pills, have operated in a world of extraordinary legal uncertainty for months. They often cannot get reliable legal advice on what is or is not illegal, because there are no recent court decisions laying out what these abortion restrictions actually do.

This problem is made worse, moreover, because not every judge hearing abortion-related lawsuits operates in good faith. The most ominous example of this problem, for anyone who needs a medication abortion, is a currently pending lawsuit seeking to force the FDA to withdraw its approval of mifepristone — an abortion drug it approved nearly 23 years ago.

That case is currently pending before a Trump-appointed judge named Matthew Kacsmaryk. Kacsmaryk, who has a history of reading the law in outlandish ways to achieve conservative results, also shares Anthony Comstock’s obsession with other people’s sexuality. In a 2015 article, Kacsmaryk denounced a so-called “Sexual Revolution” that began in the 1960s and 1970s, and which “sought public affirmation of the lie that the human person is an autonomous blob of Silly Putty unconstrained by nature or biology, and that marriage, sexuality, gender identity, and even the unborn child must yield to the erotic desires of liberated adults.”

So, to summarize, abortion providers face a crush of older and uncertain restrictions, many of which can at least plausibly be read to prohibit them from performing very basic tasks — such as receiving a supply of mifepristone in the mail. State lawmakers have prepped a wide range of bills adding new restrictions to medication abortions. And the federal judiciary and many state courts are dominated by Republican appointees who reasonably can be expected to read abortion restrictions expansively, regardless of what the law actually says.

That’s bad news for anyone who needs a medication abortion.

A overbroad reading of the Comstock law could seriously hamper access to abortion pills

The debate over what restrictions the Comstock Act places on interstate shipments of abortion pills matters a great deal, because it is unclear how abortion providers and patients can get these drugs at all if they can’t be shipped. As legal scholar and abortion expert Mary Ziegler recently told NPR, “abortion clinics are not manufacturing their own pills; they’re purchasing them from drug companies, pharmacies or getting them in the mail.”

If pharmaceutical makers cannot distribute their products to people who need them, then those products may as well not exist.

In fairness, even the broadest reading of the Comstock Act probably wouldn’t prevent a major pharmaceutical company or a large chain of pharmacies from using its own trucks to distribute mifepristone, but, at the very least, a broad reading of the law could force drug companies, pharmacists, and abortion providers to construct supply chains that avoid the mail altogether.

The Biden administration, for its part, is trying to make it easier to distribute abortion-related medications. In early January, for example, the Food and Drug Administration announced a new rule relaxing restrictions on pharmacists dispensing abortion-inducing medication. One upshot of these rules is that mifepristone will be more widely available through mail-order pharmacies.

The FDA’s new rule, moreover, follows a Justice Department memo, released shortly before Christmas, which argues that the Comstock Act should be read narrowly to permit abortion-inducing drugs to be mailed “where the sender lacks the intent that the recipient of the drugs will use them unlawfully.” This memo signals that, at least as long as President Joe Biden holds office, the DOJ will not prosecute mifepristone manufacturers and mail-order pharmacies under the Comstock Act — although it remains to be seen what happens if a Republican takes over.

(Disclosure: The Justice Department memo is signed by Assistant Attorney General Christopher Schroeder. I was briefly Schroeder’s research assistant when I was a law student.)

The Schroeder memo makes a very serious, but hardly airtight, legal argument that the Comstock Act must be read narrowly. As the memo notes, for more than a century, federal appeals courts rebelled against the Comstock Act’s sweeping language, which purports to not just prohibit abortion-related medication from the mails, but also any “paper” or “writing” that may “be used or applied for producing abortion.”

A 1915 decision by the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit held that, although “the letter of the statute would cover all acts of abortion,” the Comstock Act must be given a “reasonable construction” to permit physicians to advertise that they will perform lifesaving abortions. Later decisions imposed additional limits on the Comstock Act. Most significantly, the Second Circuit’s decision, in the hilariously named case United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries (1936), held that the act should only be read to ban items used for “unlawful” abortions from the mails.

Based on One Package and other cases that read the Comstock Act similarly, the Schroeder memo argues that the Comstock Act “does not prohibit the mailing of mifepristone or misoprostol where the sender lacks the intent that the recipient will use them unlawfully” (misoprostol is another drug that is commonly used in medication abortions). Thus, under the DOJ’s reading of the statute, even if a pharmaceutical company ships a supply of mifepristone to a state where abortion is illegal, a prosecutor targeting that company would need to prove that the shipper intended the drug to be used in an illegal abortion — and not for some other lawful purpose, such as terminating a life-threatening pregnancy or treating an illness unrelated to pregnancy.

Of course, even under this reading of the statute, some prosecutions would still be allowed. Suppose, for example, that a student at the University of Texas calls her parents in a panic because she is pregnant and abortion is illegal in the conservative red state. Her parents, who live in the blue state of New York, obtain abortion-inducing medications and mail them to her, with the intent that she use them to terminate her pregnancy. Under the Schroeder memo’s interpretation of the Comstock Act, these parents might be vulnerable to a prosecution.

Even in this hypothetical, however, it is unclear if such a prosecution would be successful — at least according to the Schroeder memo. As it notes, “some states that regulate the conduct of certain actors involved in abortions do not make it unlawful for the woman herself to abort her pregnancy.” So a prosecution of this Texas student’s parents could turn on the subtleties of state abortion law.

And the Schroeder memo could provide a safe haven to companies that distribute mifepristone and similar drugs widely, since they cannot know how each individual dose of the drug will be used, and prosecutors would have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they acted with unlawful intent.

So long as a Democrat occupies the Oval Office, federal prosecutors are unlikely to bring criminal charges that are at odds with the Schroeder memo’s reading of the Comstock Act. Indeed, it is unlikely that anyone would be federally prosecuted for distributing mifepristone in a Democratic administration. And if a rogue prosecutor did bring such a prosecution, Biden could use his pardon power to shut it down.

But the fact that the DOJ interprets the law one way today is no guarantee that it will read it the same way in a Republican administration. And, while the Schroeder memo reaches an entirely reasonable conclusion based on existing case law, there is no Supreme Court decision interpreting the Comstock Act in the narrow way it was read in One Package and similar cases. The current Supreme Court, with its virulently anti-abortion majority, could simply ignore One Package and construe the Comstock Act to ban any shipments of mifepristone altogether.

Much of the judiciary is stacked with anti-abortion judges

The troubling thing about the Comstock Act is that, if judges are willing to ignore more than a century of case law interpreting that act narrowly, the text of the law plausibly can be read to shut down public distribution of drugs like mifepristone. There are no shortage of judges, however, who don’t really need a plausible legal argument in order to implement the Republican Party’s policy goals. Foremost among them is Matthew Kacsmaryk.

Just in case there’s any doubt, the plaintiffs’ arguments in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA, the lawsuit attempting to force FDA to unapprove mifepristone, are ridiculous. For starters, the FDA originally approved mifepristone as a drug that can be marketed in the United States in 2000, and the statute of limitations to file a lawsuit challenging the FDA’s approval of a new medication is six years. As the Justice Department lays out in its brief explaining why the law does not permit Kacsmaryk to target mifepristone, there are also grave doubts that Kacsmaryk even has jurisdiction to hear this case in the first place.

Even if these problems with the Alliance lawsuit could be ignored, the plaintiffs’ arguments fall apart on the merits. One of their primary arguments, for example, is that FDA didn’t follow its own regulations when it approved mifepristone in 2000. But even if that were true, Congress enacted a law in 2007 that deemed any “drug that was approved before the effective date of this Act” to be in compliance with the relevant federal legal requirements.

I could go on, but really, what’s the point? The Alliance lawsuit rests on the extraordinary theory that an immensely controversial drug has been lawful for nearly a quarter-century — a period that includes the entire George W. Bush administration and the entire Trump administration — and, somehow, five different presidential administrations failed to notice that this drug was not properly approved.

This all said, it is difficult to exaggerate just how little Matthew Kacsmaryk is likely to care about what the law actually says. Kacsmaryk is the same judge who unlawfully ordered the Biden administration to implement a Trump-era border policy, and then, after he was reversed by the Supreme Court, did it again. He is the same judge who recently claimed that fathers have a constitutional right to restrict their daughters’ access to birth control.

So, while it is possible that this lawsuit will prove too much even for Kacsmaryk, his record suggests he might leap at this chance to impose his conservative personal views on others.

As a matter of law, it’s unclear what would even happen if Kacsmaryk rules that the FDA acted unlawfully when it approved mifepristone as an abortion-inducing drug in 2000. As Nathan Cortez, a law professor at Southern Methodist University, told me over email, mifepristone has “other FDA-approved uses completely separate” from its use as an abortifacient — it’s “approved for patients with Cushing’s syndrome and Type 2 diabetes.” So doctors most likely could still write “off-label” mifepristone prescriptions for abortion patients even if the drug were no longer approved for that purpose.

But what if Kacsmaryk issues a broad order that also purports to ban off-label use of the drug? Ultimately, the only thing we know for sure about the Alliance case is that, at some point, Kacsmaryk will issue an order concerning the legality of a very common abortion drug. And, if Kacsmaryk behaves as he has in past cases, the scope of that order will be limited only by his own desires and ambitions.

If that were not bad enough news for patients seeking abortions, this drama is likely to repeat itself over and over again as states pass restrictions, and as other litigants try to use the courts to stop the distribution of mifepristone.

The future of abortion rights in the United States, in other words, is likely to be chaos — and this is especially true for anyone seeking a medication abortion. Without Roe to protect abortion patients, those patients’ rights are subject to laws from another era, as well as newer abortion restrictions that have not been interpreted by any court. And those patients’ rights can be cut off at any time by the likes of Kacsmaryk.

0 Comments