Space is having a moment, but regular Americans don’t seem that interested.

On January 24, the James Webb Space Telescope arrived at its final destination, about a million miles away from Earth. There, the largest telescope in history is stationed to observe the cosmos, allowing astronomers to look farther out in space and further back in time. The Webb took over a decade of work and billions of dollars, but the timing of its launch coincided with a record-breaking year of space activity, in addition to growing cultural and commercial interest.

Some believe we are at “the dawn of a new space age.” 2021 was a big year for rocket launches, with activity nearly rivaling that of 1957, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 and kick-started the space race. Last year was a turning point for commercial space tourism and exploration, with various billionaire-backed ventures embarking on recreational spaceflights.

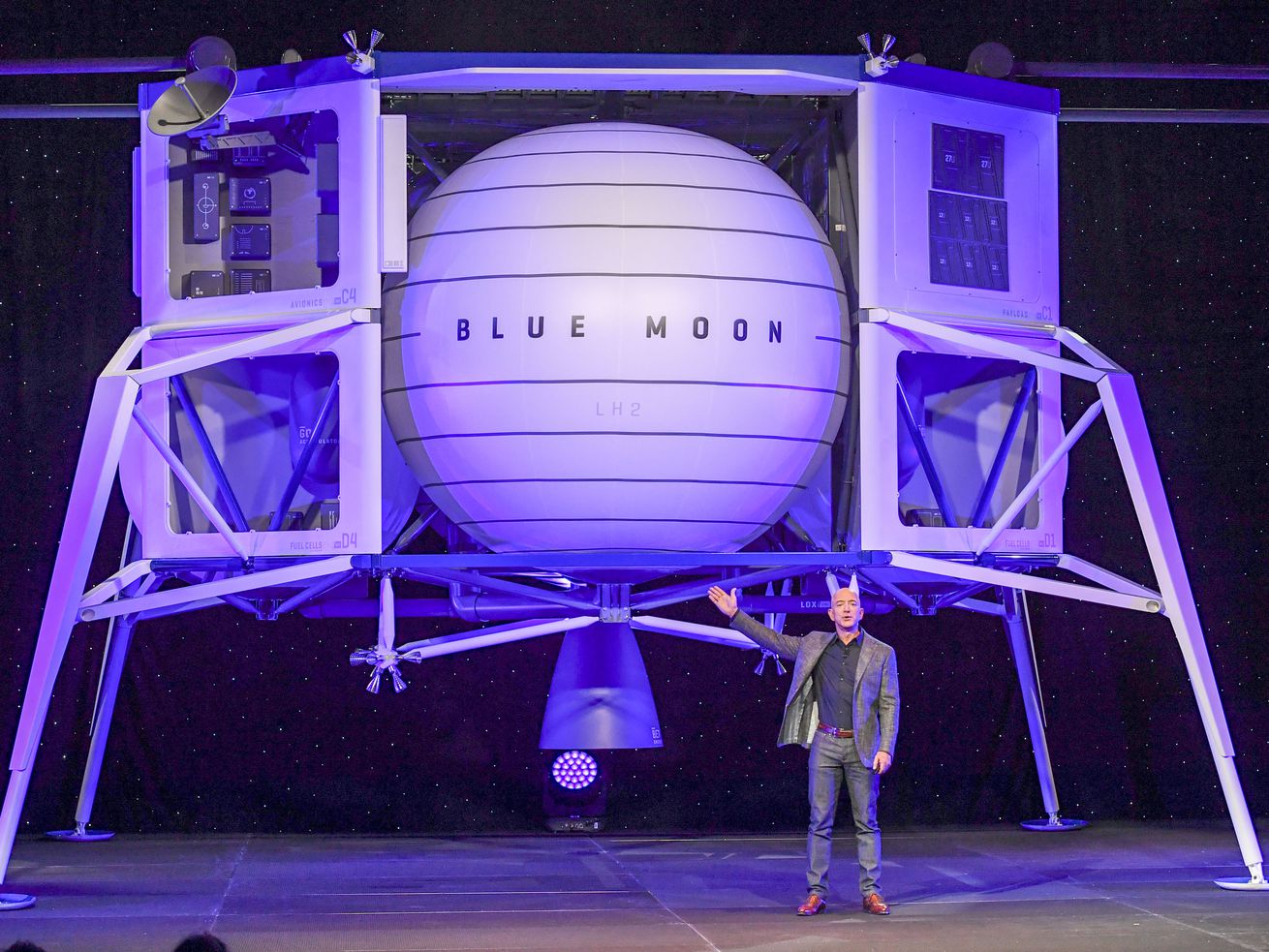

In July, Richard Branson of Virgin Galactic, accompanied by five passengers, took a 90-minute trip about 50 miles into Earth’s atmosphere. Fellow billionaire and Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos flew out 10 days later on a 10-minute tour. His rocket, carrying three other space tourists, surpassed Branson’s distance to reach the Kármán line, which is internationally recognized as the edge of space. And in September, Elon Musk’s SpaceX launched a four-person civilian crew into Earth orbit for a three-day journey. (Musk himself was not on board; billionaire Jared Isaacman, who helped finance the mission, was.)

Some industry experts say the success of privately funded endeavors like SpaceX and Blue Origin has piqued the attention of private investors. Investments in space startups nearly doubled from 2018 to 2019, according to analytics firm BryceTech, and space companies raised a record $14.5 billion in 2021, reported CNBC. The US government, too, seems interested in expanding NASA’s foothold in space. This year, the agency has plans to launch a space station into the moon’s orbit, and will collaborate with SpaceX to send an astronaut crew to the International Space Station.

It’s not just America and its billionaires, however, that are clamoring to make gains in space. Russia and China are close behind, although the latter’s wealthiest citizens have kept a much lower profile. The two countries have agreed to collaborate on lunar missions, and are looking to build a research station on or around the moon. Russia and Europe are also planning to launch a rover to Mars next year, while South Korea, with the help of NASA, is scheduled to send its first mission to the moon.

A new era of space technology and exploration is upon the world, one that could rival the 1960s in historical significance and magnitude. It’s unclear, however, if these advancements will be met with the cultural fervor that made the last Space Age feel so distinct. This time, the public interest in space is driven less by spectacle and more by the agendas of highly influential billionaires.

Despite all the recent hullabaloo, regular people don’t seem to be very excited about the cosmos. Most Americans want the US to remain a leader in space exploration, but a Pew Research poll from 2018 found that the public was evenly divided on the future prospect of space tourism. A majority also think that NASA should prioritize monitoring the Earth’s climate and atmosphere for asteroids and debris above sending manned trips to outer space. In fact, it seems as though citizens, stuck at home on Earth, have grown resentful of billionaire-led space tours. These publicized missions have received their share of online backlash.

People have argued that Bezos’s or Branson’s money should go toward pressing earthly causes, like fair wages for workers, taxes, medical research, climate change, or world hunger. These arguments aren’t new; similar concerns were raised during the first Space Age. These expeditious joyrides, however, can seem even more unnecessary during a pandemic that has exacerbated the wealth gap and weakened the American health care system.

That being said, space is much more than a zero-gravity playground for the wealthy. Space technology is key to our modern communications infrastructures, climate monitoring capabilities, air travel, security systems, and much much more. If this is the beginning of the 21st century Space Age, why are Americans so disillusioned with its potential? Is there reason to hope that our lives on Earth will be all the better for it?

The Space Age, then versus now

In the decade leading up to the Apollo moon landing, Americans were captivated by science fiction and the prospect of exploring outer space. Some historians interpreted this cosmic fascination as a coping mechanism in the aftermath of World War II and America’s ongoing wars in Asia. Space, as an unexplored realm, was a destination for escape, fantasy, and even fear.

“It has often been suggested that the atomic bomb was responsible [for the boom in science fiction], creating at once an appetite for vicarious scientific adventure and a need to externalize fear,” wrote space historian Walter McDougall. It was, in hindsight, a form of cultural anticipation, fueled by a mass media obsession with outer space. It was reflected in the public frenzy over UFO sightings, and in works produced by Hollywood, Disney, science fiction writers, major magazines and newspapers, avant-garde artists, and fashion designers. Space was on everybody’s mind. And after the US’s first successful manned mission to the moon, the prevailing narrative, in retrospect, was one of unity — of a common dream being achieved.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23208305/GettyImages_121104105.jpg) Getty Images

Getty Images

“The Apollo 11 moon landing was such a landmark event because, and this sounds clichéd, it was a dream that became real,” said Stephen Petersen, an independent scholar who published a book on Space Age aesthetics. “There was so much media — in pop entertainment, the art world, news coverage — that envisioned space exploration and rocket launches years before anyone thought it possible. So I can imagine how seeing it unfold was significant to people because of the imagery, the films and books that preceded it.”

This wasn’t entirely true. Public opinion polls revealed a majority of Americans opposed the Apollo Program “consistently throughout the 1960s,” Alexis Madrigal reported for the Atlantic in 2012, despite the positive press and political leverage it generated. “We’ve told ourselves a convenient story about the moon landing and national unity, but there’s almost no evidence that our astronauts united even America, let alone the world,” wrote Madrigal. “Yes, there was a brief, shining moment right around the moon landing when everyone applauded, but four years later, the Apollo program was cut short and humans have never seriously attempted to get back to the moon ever again.”

Citizens thought space exploration was too expensive, with the exception of a poll conducted after the first Apollo landing in 1969. Scientists, too, saw no need to rush a trip to the moon with humans, or for the government to focus on space over other earthly scientific endeavors. NASA’s budget was also sharply reduced after Apollo. While the agency has steadily received more federal money throughout the 2010s, it isn’t close to receiving the apex of funding that made Apollo possible. Americans, to that end, have seemingly begun to regard the cosmos with much less wonder and excitement, although public support for the moon landing has only grown over time.

With the US in the midst of another space boom, it’s possible people will be unenthused by — if not downright opposed to — federally funded exploration. This time, its cultural novelty might’ve worn off for good. Part of that is a result of our fractured media ecosystem: Fewer people watch shuttle launches, which have become much more frequent. What audiences watch is no longer dictated by television programming, and the entertainment value of a new Netflix or Disney+ show likely outweighs the lengthy lead-up to a rocket takeoff.

It doesn’t help how modern media is a mishmash of familiar aesthetics, tropes, and themes. Frequent reboots of old shows and franchises, like Star Wars and Dune, contribute to this alienating circumstance, where nothing feels particularly innovative or exciting. Much of the aesthetics and art produced during and after the 1960s Space Age were experimental and visually striking, according to Petersen. Futurism, for example, encouraged artists to liberally engage with new technologies and materials, and was popularized by influential figures like Andy Warhol and David Bowie.

The modern ’60s revival in fashion and style has brought Space Age imagery and design back to the fore, but largely without its futuristic edge. The pop star Dua Lipa coined it best: It’s a form of “future nostalgia.” This aesthetic return is mostly style with little substance, and encapsulates the fleeting, anachronistic state of modern trends. It’s hard for us to collectively care about anything when social media discourse and the news cycle move so fast. We don’t have the patience for space or the protracted timeline it operates on.

“Most space companies are working on a decadeslong timeline,” said Michelle Hanlon, co-director of the University of Mississippi’s Center for Air and Space Law. “The startups getting funding might seem mundane to people, like satellite imagery and telecommunications.” In fact, Hanlon added, most people have taken for granted the advances in space technology that make modern life possible. (Satellites, launched with the intention of expanding internet access across the globe, are crowding up the night sky, to the ire of astronomers.) Nearly every part of it bears some relation to space.

Like it or not, billionaires — and private enterprises — will define much of the modern space race

NASA has increasingly outsourced space-related work to private companies; it’s likely a cost-cutting measure, and also leaves room and support for the emergence of a robust commercial space sector. The agency, for example, has announced that it would buy lunar dust samples harvested by private contractors for independent assessment. CNBC reported that the agency has paid SpaceX and Boeing more than $3.1 billion and $4.8 billion, respectively, since 2014 to develop launch capsules for American astronauts.

These private partnerships with NASA, according to Laura Forczyk, founder of the space consulting firm Astralytical, are a turning point for the commercial space sector. “NASA has always contracted out work. The Apollo rockets, for example, were built to the agency’s specs and standards,” she said. “We’re now seeing a different approach to government partnerships. Instead of buying hardware, the US is looking to fund or buy entire services.” To Forczyk, this seems like “a concerted effort to build a commercial industry.”

In recent years, a handful of American billionaires have, for better or for worse, drawn the public’s eyes toward the skies again, sometimes to the chagrin of the public. Many working in the space sector, though, like Hanlon and Forczyk, are grateful for the presence of Bezos, Branson, and Musk.

“I’m actually thankful for the billionaires because they’re taking a long-term approach,” Hanlon said. “They’re spending money on space that taxpayers wouldn’t want to spend.” Without these privately funded endeavors, they claim, the prospect and pace of space exploration would be much slower.

Forczyk predicts that space tourism will develop as an industry similar to commercial air travel, with wealthy individuals as the early adopters. “Over time, these trips will become accessible to regular people,” she said. However, the purpose of these tours, beyond their recreational aspects, are still murky. So far, these commercial trips have yet to produce any major scientific insights, although they could contribute information for future human exploration. These tours, reported Recode’s Rebecca Heilweil, have been marketed as potential opportunities for scientific experiments. Last year, a Virgin Galactic flight brought plants to space and tested how they responded to microgravity.

It’s unlikely, however, that scientific discovery for the greater good of humanity is the sole force driving billionaires toward the cosmos. (After his space tour, Bezos suggested that, decades from now, heavy and polluting industries could move their manufacturing to space to reduce environmental harms. Meanwhile, Amazon was responsible for 60 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2020.) Other motivating factors could be ego, power, or the ambitious ability to chart their own extraterrestrial destiny. In 2016, Musk declared that “history is going to bifurcate along two directions.” One path is to stay on Earth and risk an “eventual extinction event.” The alternative is to become what he described as a “spacefaring civilization.”

Spacefaring comes at a steep cost — one that is inaccessible to most citizens, even if they cobbled together a lifetime of savings. The average American’s annual salary is about a tenth of a $450,000 Virgin Galactic ticket to space. Even if Musk’s far-fetched vision is intended to be a humanistic warning, it’s not hard to figure out why the public seems so impassive about outer space. From down here, space travel appears to be an escapist fantasy for the rich.

Yet there’s still a romantic idealism attached to the universe, in its ability to foster collective unity and wonder. In observing Earth from afar (farther than the route of current commercial spacecrafts), former astronauts described experiencing “a profound sense of awe and a dramatically different perspective on life.” Space, as a destination, seems intangible to most, but that doesn’t mean it’s beyond our imagination. Perhaps, as the Webb telescope might soon reveal, there’s something more valuable to be learned from afar.

0 Comments